2016 Reading List: Too Much, Too Fast

2016-11-20 13:48:03.315791

The last time I offered up a list of book recommendations, it was 2012. Most people reading this, of course, weren’t even born then, so you can’t imagine how intense those days were. We were truly living on the edge: overloading our senses with new experiences, making peace with our tangled webs of karma, and waiting for Daniel Pinchbeck to ascend to his rightful throne as Quetzalcoatl, Serpent God of the New Dawn. Somehow that didn’t happen, and Pinchbeck, like the rest of us, still suffers the indignity of having to work for a living.

This list was easy to assemble because the only books I currently own, I’ve bought since 2012. The only hard part was narrowing it down.

The Pentagon of Power, by Lewis Mumford. This is the second volume of Mumford’s “The Myth of the Machine,” and to him, the fourth of a series on how technology has altered human development. No prior reading is necessary to be stunned silent by this book, though. Mumford is a patient teacher with a world-spanning curriculum to impart. I can’t think of another single book I’ve learned more from in the past four years.

Seeing Like a State, by James C. Scott. This is a book that both confirmed my suspicions, and changed my mind about many things. Scott demonstrates a failure mode that recurs throughout history and emerges from a broad spectrum of ideologies: a blind faith in technology and central planning, and the willful delusion that human subjects can be reduced to legible -- and thus, predictable -- quantities. He makes his case through richly written historical studies, full of human nuance and operational insights. (Scott’s other book, The Art of Not Being Governed, is equally excellent.)

The Invention of Nature, by Andrea Wulf. A love letter to a peak moment in human civilization, and a portrait of a truly remarkable man. Alexander Von Humboldt came closer than most mammals to fitting the entire world between his ears. His legacy is nearly impossible to encompass, yet Andrea Wulf does it justice, her prose is impeccable. The focus of this book is on three of his most ambitious research expeditions, which frame an intoxicating account of his life, his work and his world.

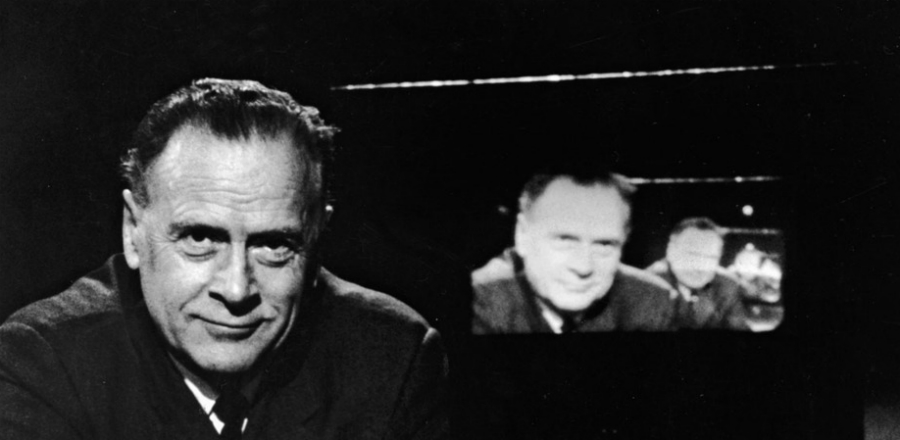

From Cliche to Archetype, by Marshall McLuhan & Wilfred Watson. Like most McLuhan fans, after talking about him for years I eventually decided to start reading his work. The Mechanical Bride was damn good and of course, Understanding Media is the best place to start for McLuhanism proper. Yet when people ask me where to begin, I recommend From Cliche to Archetype, a quirky, wide-ranging master class from an unusually forthright version of Professor O’Blivion. McLuhan is always having fun, but this is one of the few times his chuckles aren’t coming at the readers expense.

The Underground Empire, by James Mills. The most entertaining, unbelievable, and carefully observed book on the global drug market I’ve ever read. You should be suspicious of James Mills. The man is a novelist by trade, and claims that he’s been given unlimited access for several years to the DEA’s most clandestine and powerful unit, CENTAC. This is all problematic, to be sure, but the real problem is how page after page checks out. An embarrassment of riches.

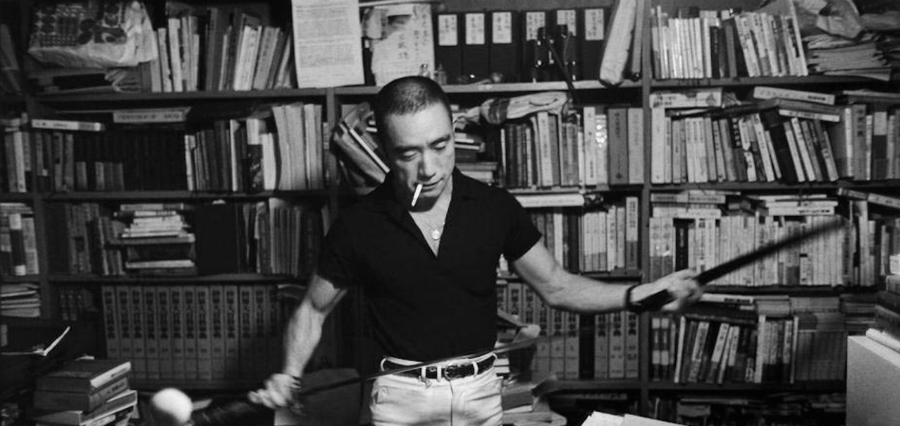

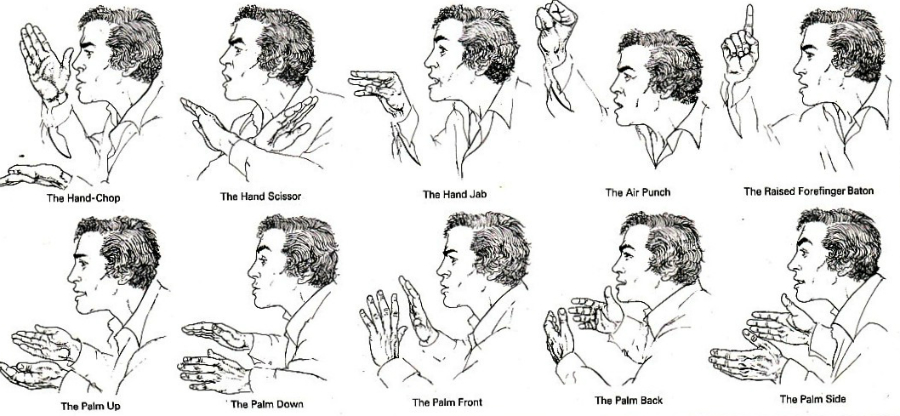

Manwatching: A Field Guide to Human Behavior, by Desmond Morris. Even better than it sounds. An endlessly readable book -- get the ‘77 hardcover version, they’re cheap used -- this is something I wish I’d had when I was 8 years old. The anthropology is wry and often profound, and the illustrations are a gorgeous photo montage of humanity. The fact this is not a school textbook is proof that our culture is a conspiracy against us.

The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light, by William Irwin Thompson. One of the few philosophers I can abide reading, Thompson has always kept his theory grounded in the dirt of biology and history. He’s written many brilliant books but this is, by far, his best work. Having read it twice I remain at a loss to explain what, precisely, this is “about” -- suffice it to say the subtitle only hints at the scope and depth: “Mythology, Sexuality and the Origins of Culture.” As a child raised on Joseph Campbell products, this was valuable de-programming.

Lyndon LaRouche and The New American Fascism, by Dennis King. This was clearly intended as a scathing expose, but I came away from this with a newfound respect for LaRouche. Dennis King is a dedicated researcher and this book is crazy thorough. Anyone interested in the interpersonal dynamics, daily operation and maintenance of cults needs to read this. King’s analysis of LaRouche’s private intelligence and security operations is also first rate. This is pretty close to a manual on how to become a national security threat. Read it.

The Strength of the Wolf, by Douglas Valentine. A blunt investigation that documents the doomed, compromised & corrupted Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Valentine is no stranger to law enforcement or the Deep State, and his access makes for sensational reading. This is an indispensable oral history, packed full of details you not find anywhere else.

Remote Viewers, by Jim Schnabel. The best book on the subject by far; also one of the only accurate ones available. Schnabel stays admirably agnostic about the narratives and sticks to Actual Journalism. The result is carefully documented history with plenty to disturb both skeptics and true believers. In closing, Jon Ronson is junk food trash on par with Malcolm Gladwell and Thomas Friedman.